A teacher, living a life of penance

Krishnan Murugan, a retired teacher, lives alone in a Central Section chalet. He was making a dish of vegetable curry at home when we arrived, watching over a boiling pot whilst seated on a lounger due to his immobility.

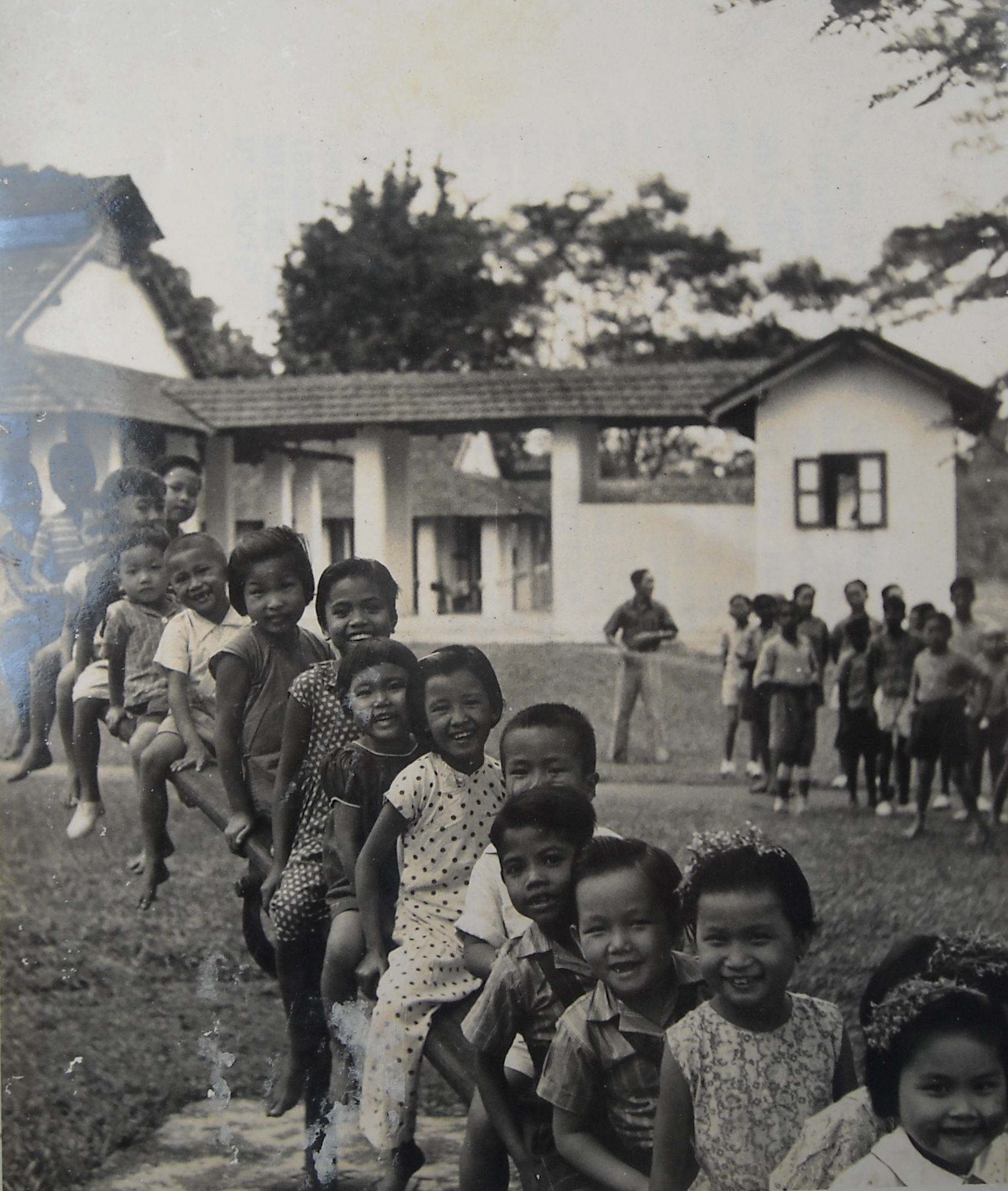

Krishnan is very happy when he recalls of his teaching life. (photo by Mango Loke)

He was born in India in 1924, however his parents soon left for Malaya and brought him along, eventually settling down in Malacca. Krishnan is the eldest child in the family and his father worked for the government as a sanitation worker. He has four younger sisters and a little brother. When he was in primary school, he began suffering from fungal infection and discolouration of the skin all over his body, but neither did Krishnan nor his family suspected leprosy. It was only when the affected areas had become swollen that they started to link his condition to leprosy.

But then, life was hard during the Japanese occupation. He said his family could not do much besides sending him away to a hut by the river, where food was delivered to him every day. In 1948, an official of the British colonial government learnt about this and had him taken to the Valley of Hope. Initially, Krishnan’s father did not visit him because he mistakenly assumed that he had been sent to a remote island. He visited Krishnan once or twice – with tears streaming down his face, every single time – when he found out that Krishnan was actually sent here.

Growing up in wartime, Krishnan was forced to leave school in Primary 3, before resuming his education when he came to the Valley of Hope. However, he only made it to Primary 4 because according to the rules, patients must leave school when they turn 18. Nonetheless, after graduating, he was assigned to teach in the settlement’s Travers School since he could read and write, whereas most of the other inmates in the settlement then were illiterate.

He said that there were only 13 teachers, including a Malay teacher, a Tamil teacher, and two Mandarin teachers – due to the fact that a majority of the students in the settlement were ethnically Chinese. At that time, there were about 250 students and he was in charge of the English and Tamil classes for Primary 1. He even taught Malay for some time when there was a critical shortage of teachers. Given the limited space for teaching, some hospital wards were partitioned into temporary classrooms.

The children of the settlement are happy and active despite being affected by leprosy.

(photo courtesy of Lai Fook Hin)

“Students then hardly studied. The 14-to-15-year-olds and the 12-to-13-year-olds were all in the same class.” Given that students of all levels were placed together in one class and the school had no system in place for teacher training, he just taught using textbooks and assigned simple homework such as fill-in-the-blank questions and arithmetic problems. He would also give them spelling tests on simple vocabulary words at class. Krishnan said he was strict as a teacher and would use a cane to punish the students if they were naughty, especially the indigenous students who could never sit still and loved running around. “Otherwise, the class would be out of control because not all students are the same.”

He told us that the students had English and Malay classes from 8 o’clock in the morning till 12 noon, followed by vernacular language classes from 2pm to 4 pm. So, his life was quite busy – every day when he finished the morning classes by noon, he had to teach Tamil after his lunch break. “When the bell rang at 12 o’clock, they must go for lunch. After lunch, they had to go for Tamil class at 2pm. There was no time. They were more relaxed only when exercising.”

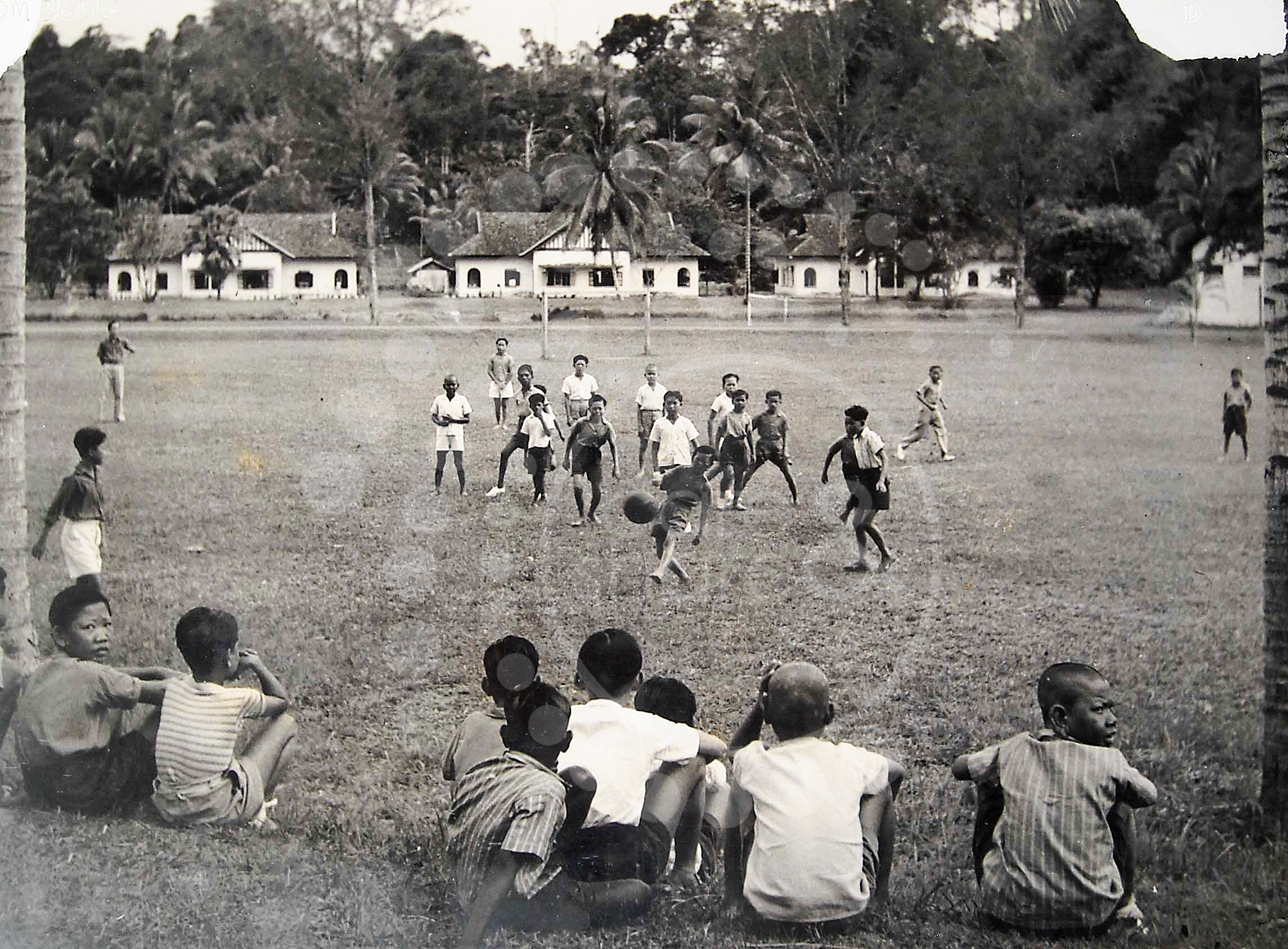

The boys play games such as football and hockey. (photo courtesy of Lai Fook Hin)

The settlement used to be abuzz with activities. Every afternoon, there would be students running on the field, or playing football and basketball. The Sports Day, held once a year, was the most anticipated event for the students. According to Krishnan, the students would be divided into four houses – all distinguished by different colours – to compete with one another on the annual Sports Day.

Then, the number of students gradually decreased as many students chose to be discharged from the settlement, and eventually the number of students dwindled into two. So, the school closed down during the term of former Deputy Director Dr Kumar (1961-1977), and that’s when Krishnan stopped teaching too. His monthly allowance, only RM30 at the beginning, was raised to RM175 before he left the job. After that, he was arranged to work as the Inmate Store Keeper for the same amount of salary.

He described, in retrospect, what it was like to live here: “In the past, we could not trade goods like eggs with the ‘outside world’. We produce things here, we eat them here, and we sell them here, because they feared that the produce would be contaminated. No exception, even for rambutans. When our rambutans ripened, we could only eat them here inside the settlement. We could not sell the rambutans to those ‘outside’. After the Malaya independence, Dr K. M. Reddy came and opened up this place to the outside world. If not for Reddy, there would be no such thing as a policy that allows everyone to step out of the settlement.”

Dr Reddy came all the way to Malaya from India, in 1952, to serve in a hospital controlled by the British colonial government. He was one of the founder members of the Malaysian Medical Association and the Medical Superintendent of the Sungai Buloh Settlement from 1957 to 1961. Having served in the Valley of Hope for four years, he had brought many changes to the settlement, despite the short duration of his service here. To eliminate society’s prejudice towards leprosy patients and to encourage patients’ contact with outsiders, he initiated an annual Open Day at the settlement in 1959. He also encouraged inmates to grow and sell flowers to outsiders so that they might generate more income. Hence, many inmates still miss him to this day.

In 1966, Krishnan married a woman who was of half Chinese and half Orang Asli (aborigines) parentage, who had a son and a daughter from her previous marriage. According to Krishnan, she was not a leprosy patient. However, after her daughter contracted leprosy, a foreign-born police officer took her and her son along to the Valley of Hope. “The white people were very strict, you know? If one person had the disease, the whole family has to be admitted to the settlement.”

When Krishnan first moved out of the hospital ward, he was assigned to a chalet for three, and subsequently the Marriage Quarters after getting married. He and his wife lived together for twenty years but she left the settlement sometime in 1990 to babysit her grandchildren in Pahang. His wife has since passed on but he is still staying in the Marriage Quarters where they used to live.

In the middle of our interview, an Indian healthcare worker arrived on a motorcycle to deliver Krishnan some plain rice. We soon learnt that this man delivers Krishnan newspapers every morning and food at noon. Krishnan cannot leave his house due to lower extremity impairment, so he has engaged this man to run errands for him, in return for some money.

In the 1950s when Krishnan used to teach in the school, there were about 400 Indian inmates in the Valley of Hope. Every day after work, they would gather at the Indian Mutual Aid Association and the Indian Club to play some cards, listen to the radio and have a chat. However, these two clubs have closed a long time ago. Now, there are only five Indian inmates in the settlement – Four of them are staying in the hospital ward while Krishnan is the only one living in the chalet.

Krishnan uses the walker to go outside to water his plants. (photo by Mango Loke)

Due to language barriers, he barely has any friends to chat with in the settlement. His chalet is usually quiet with hardly any visitors. He would rest in a lounger by the door, reading newspapers or relaxing with his eyes closed, and watch some news on the television to while away time. Krishnan is a devoted Hindu and has been a vegetarian since he was a child. When he had just been admitted, he was advised by the doctor not to rely solely on vegetarian food but he stuck to his vegetarian diet anyway. These days, when he is in good spirits, he would make a vegetarian dish or curry.

All of his life, Krishnan has been haunted by a hulking shadow – the ancient belief of sin and guilt. When asked of what he thinks of his life, he said, “I think leprosy is a punishment because one must have sinned badly so as to be afflicted with this disease. I used to pray three times a day, but only twice a day now since I have become old and weak.” It is only through faith can this lonely, retired teacher find peace inside.

Krishnan praying to his Hindu deities. (photo by Mango Loke)

Narrated by Krishnan Murugan

Interviewed by Chan Wei See & Wong San San

Written by Chan Wei See

Translated by Zoe Chan Yi En

Edited by Low Sue San